ABDENOUR ZAHZAH

The director discusses his film, True Chronicles of the Blida Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in the Last Century, when Dr Frantz Fanon Was Head of the Fifth Ward between 1953 and 1956

Words

EMMA BOURABA

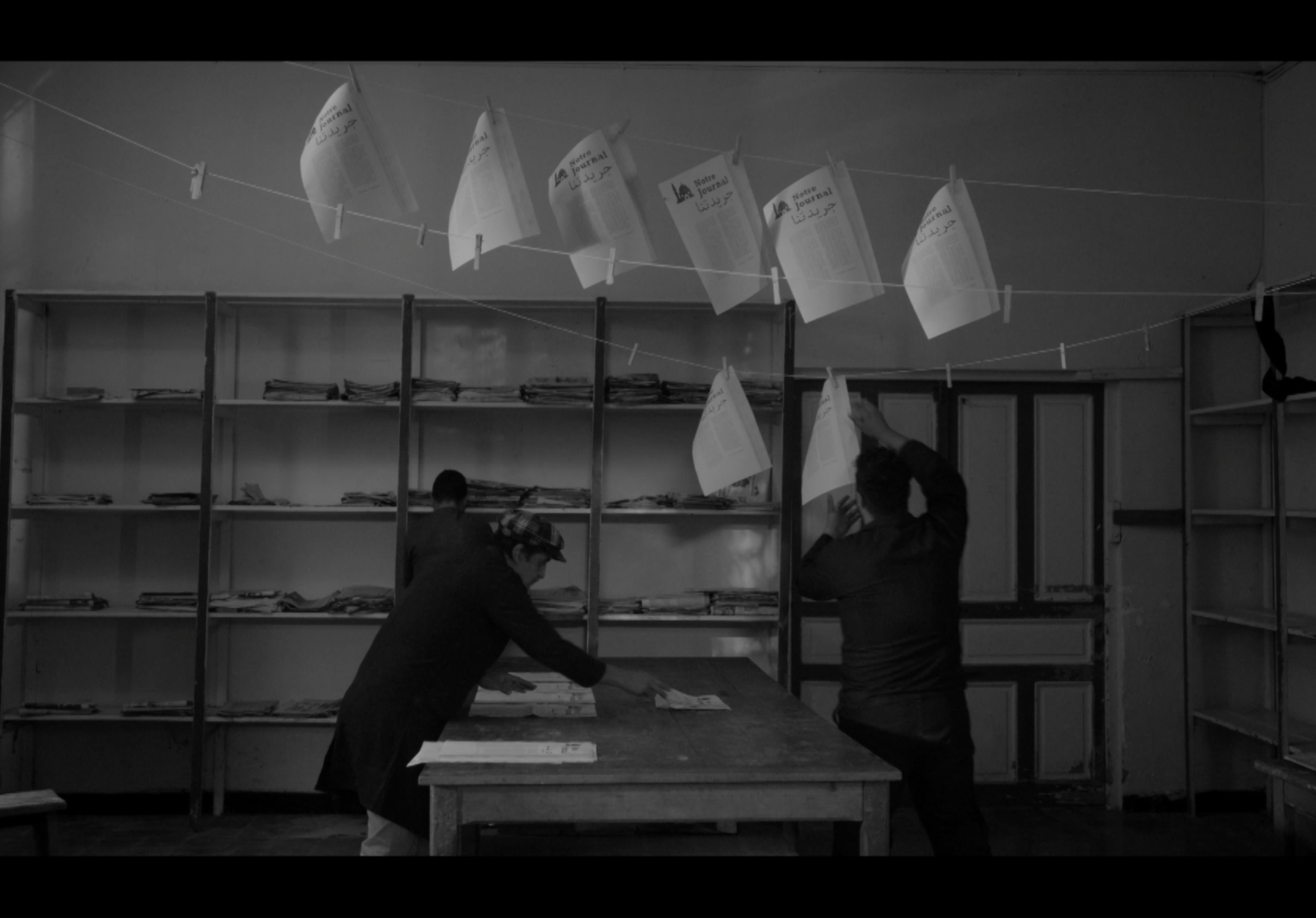

Abdenour Zahzah’s biopic brings a new perspective on the legacy of psychiatrist and revolutionary Frantz Fanon, honing in on his pivotal time in the city of Blida, Algeria, from 1953 until 1956, which was then under French colonialism. The Algerian director’s film offers a striking insight into Fanon’s psychiatric practice grounded in his anti-colonial commitment. Shot on-site at Blida Joinville Psychiatric Hospital, Zahzah vividly captures Fanon’s relationship with his team and patients, while showcasing how he came to join the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) in November 1954.

This black-and-white fiction is based on extensive archival research and gathering of multiple testimonies. Zahzah delivers an emotionally captivating portrayal of the complex figure of Fanon, enacted by Alexandre Desane, while the way he delves into Fanon’s psychiatry methods offers a fascinating entry point to his anticolonial legacy.

Following his resignation from the hospital, Fanon was deported and moved to Tunis where he openly joined the FLN. The Pan-Africanist and Marxist humanist thinker joined the editorial team for the FLN newspaper El Moudjahid and later served as an Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government. Fanon’s legacy continues to have a profound impact, especially through his critically acclaimed works ‘Black Skin, White Masks’ (1952) and ‘The Wretched of the Earth’ (1961). Fanon died in December 1961 from leukemia in the US and he is buried in a martyrs' cemetery in eastern Algeria.

Zahzah, who served as the director of the Cinémathèque of Blida from 1998 to 2003, has long been fascinated by Fanon. His filmography includes the documentary Frantz Fanon, Mémoire d’asile (2002) and La Longue Marche vers le Nepad (2009). This first feature-length fiction film about Fanon’s years in Blida has been critically acclaimed and premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2024. We speak with Zahzah on the making of this important work.

The film portrays Fanon at Blida Joinville Psychiatric Hospital. Why did you choose this timeframe and lens?

I chose to tell the story of Fanon as a psychiatrist and clinician in Blida because it was here that as an anti-colonial psychiatrist his life shifted as he joined the Algerian independence movement. In Blida, he dealt directly with cases of psychiatry linked to the violence of the war, which he later described in the fifth chapter of his book, ‘The Wretched of the Earth: Colonial War and Mental Disorders’.

How did you compensate for the lack of visual archival material of Fanon?

The lack of archival images of Fanon, as he lived in hiding from age 28 when he became an Algerian militant, inspired me to create a fiction film. Fanon was sorely missing from the cinematic album of Algeria, and even the world. I gathered the hospital archives while making the documentary, Frantz Fanon, Mémoire d'Asile (2002) with Dr. Bachir Ridouh, including the journal Fanon created at the hospital, Notre Journal. I also met a large number of nurses from Blida who had worked with Fanon, as well as his editor François Maspero and Algerian politicians with whom he collaborated, such as Réda Malek, editor of El Moudjahid newspaper. Fanon contributed several articles that were later published by Maspero under the title ‘Frantz Fanon – For the African Revolution’.

How was your collaboration with actor Alexandre Desane who plays Fanon?

Alexandre Desane was already passionate about Fanon; we imagined Fanon’s attitude towards his healthcare team and his patients. We had to reinterpret part of Fanon's personality as a doctor. From testimonies gathered, Fanon was lively and passionate, interested in any subject. However, for the portrayal of Fanon as a doctor, there had to be some distance as doctors are required to “play a role” in their therapeutic work to establish trust with their patients. Unlike other doctors of the time, Fanon was the only one entering a courtyard filled with patients. We tried to show all this while highlighting, through dialogues and small gestures, Fanon’s obsession with his work.

“Only Algerian independence could be the first therapeutic condition for Algerian patients”

What did Fanon’s son, Olivier Fanon, bring to the film?

It was essential for Olivier Fanon to be in the film. I was hesitant to ask him to appear in the film but I couldn’t find an actor to play Marcel Manville, the great anti-colonial lawyer and Fanon’s childhood friend. He agreed without asking to read the screenplay, even though it was about his father. Olivier Fanon is deeply respectful of the work of others, from directors to writers. He is truly a beautiful person, just like his father certainly was.

Which methods did Fanon put in place as an anti-colonial psychiatrist?

Fanon learned everything at the Saint-Alban hospital, under Catalan psychiatrist, Francesc Tosquelles. He added to Tosquelles’ psychiatric practice the colonial alienation dimension, which he encountered in Blida. Under Fanon’s initiative, the mosque of the hospital was restored to its original role as a place of worship. He recruited an imam to lead prayers for the Muslim patients. He also recruited famous singer, Abderrahmane Aziz, to reintroduce Algerian culture at the hospital. Reconnecting patients with their cultural and emotional environment was a therapeutic act. But Fanon also quickly understood, as explained in ‘Letter of resignation to the Resident Minister’, Robert Lacoste, that any therapeutic work would be in vain since the stabilised patient, once discharged, would find himself in a “toxic and cursed” environment. Thus, he realised that only Algerian independence could be the first therapeutic condition for Algerian patients. Acting on his convictions, Fanon decided to become an Algerian militant and joined the Algerian National Liberation Front.

Could you expand on the relationship between Fanon and Abderrahmane Aziz?

Abderrahmane Aziz was a famous singer who lived in Blida and met Fanon, who recruited him as a nurse. Aziz understood Fanon’s approach and formed a theatre and singing troupe with the patients. The Muslim patients, who weren’t very engaged with the cine-club Fanon had set up, were transformed by Aziz’s theatre performances. Fanon also took the opportunity to learn Arabic from Aziz, wanting to understand the patients without relying on the nurses’ translations. Including him in the film was an obvious choice. Later, I discovered a filmed archive [footage of Aziz performing at the hospital is included in the film] by Georges Daumezon, a Breton psychiatrist who visited Fanon in Blida in 1954.

How did you approach fictionalising Fanon's activism?

It was a long process of reflection to stage Fanon’s work in Blida. To understand how Fanon admitted militant patients, it was necessary to explain this process through the means of fiction. Because, at the time, especially in colonised Algeria, even head doctors weren’t authorised to admit patients or sign their discharge papers. Everything went through the prefect, which meant the police. I had to include a sequence showing what involuntary placement was with the police bringing in a patient. In the meantime, Fanon came up with a brilliant idea to establish the "day hospital" for short-term free cures, where doctors could sign without involving the police. It was thanks to this administrative trick that Fanon could treat Algerian activists under false names.

Words EMMA BOURABA